FREE AT LAST, FREE AT LAST

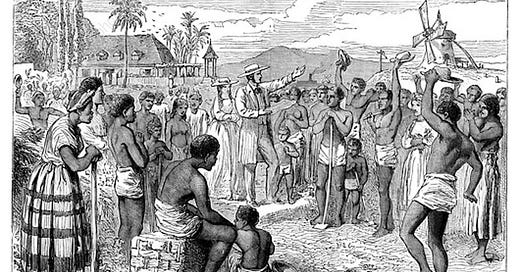

On 1 August 1838, after 200+ years of the chattel enslavement of three million kidnapped Africans – followed by a bizarre four years of quasi-emancipation called the Apprenticeship Period, which Eric Williams called “slavery minus the whip” – Black people were finally free. Not equal, mind you; that would be an ask too far. And, hey presto, Britain pulled off the greatest piece of national rebranding the world had ever witnessed. As if a curtain of forgetfulness had been dragged across the face of history, the great enslaver repositioned itself as the great liberator. At a stoke, redemption had vanquished guilt. Hallelujah!

The great liberator was also the great payer of reparations. Not to the enslaved, of course, but to the enslavers who, heavily in debt to a miscellany of British banks and financers, saw themselves as the victims. As usual, the banks were ‘too big to fail’; such failure might well collapse British banking. There was also the ticklish issue that enslaved persons were private property that the Crown couldn’t arbitrarily confiscate.

The solution? About £20m (or approximately 4 per cent of Britain's GDP) was paid out to ensure every single slave owner was recompensed. Today, 4 per cent of the British GDP is about £90 billion. The debt was finally repaid in 2015.

EXODUS

A large number of plantations failed, others were abandoned and some islands rapidly diversified into different crops such as bananas. But still, large British consortia bought up clusters of plantations to make the whole business more business-like (which they did), and in many colonies sugar remained king. Tiny Barbados, where there was nowhere to go, saw life continue almost as before.

As for the newly liberated, those who could, gave the finger to the plantations and moved off the estates. Those who couldn’t, kept their fingers to themselves or emigrated to greener pastures (such as Trinidad). Old memories mixed with new desires to motivate them to reshape their lives as free men and women, hustling a new kind of living, pressing for better wages and learning to live with a sense of purpose and agency, even in the shadow of the cane fields.

SUGAR PLANTER SEEKS LABOUR FORCE

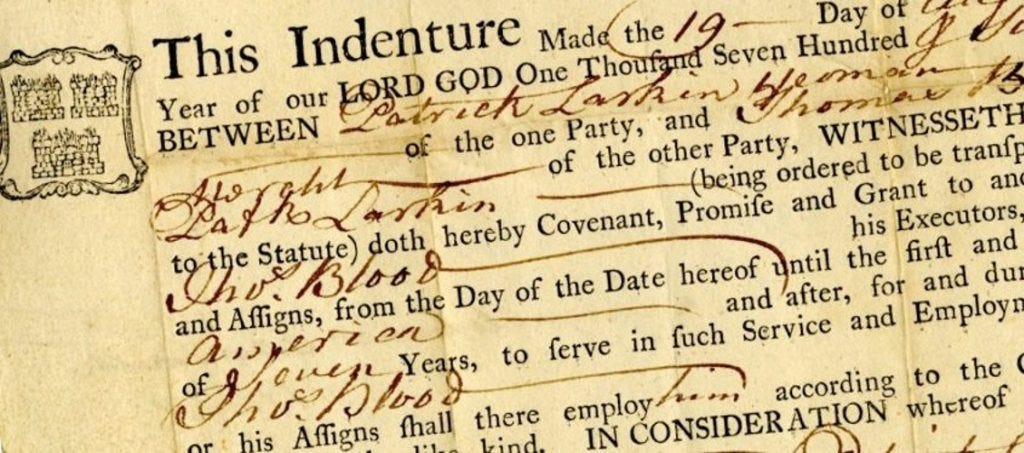

Emancipation or no, said cane fields still needed a vast labour force to plant, weed, cut, crush and turn fattened stalks of cane into the muscovado gold of sugar. In Britain's vast empire, on which the sun never set, the appeal of four to six years with a pocket handkerchief of land or repatriation at the end found favour with an endless supply of the hungry and the desperate (hoping for better than to be poorly paid, barely fed and brutally treated). Sundry crop failures, religious squabbles, ethnic battles, unending poverty and wretched lives drove tens of thousands of East Indians and Chinese but also some Madeirans into the open maw of indentureship.

MEET THE MADEIRANS

Madeira (see above map) sits in the middle of the North Atlantic Ocean about 320 miles (or 540 kilometres) West of Morocco. This slip of an island had been colonised by Portugal and was where Columbus’s father once traded; indeed, where the explorer himself had met his bride. The island was in the sugar business even before the explorer had crossed the Atlantic. Though it was by no means a part of the British Empire, it was unusually close to Britain due to interlaced trade links and family connections. Many British companies and citizens owned shares in its lucrative madeira wine businesses. Indeed, during Napoleon’s reign, Britain rerouted its navy to protect the little island against the French.

The Madeirans who left were fleeing religious persecution and famine – a period known as o ano de fome – and saw British Guiana and Trinidad (mainly) as places worth seeking refuge in. Despite a rocky start, when many people died from dysentery, yellow fever and malaria, whole villages made the journey over: in total about 45,000 people (over 15 per cent of the entire island).

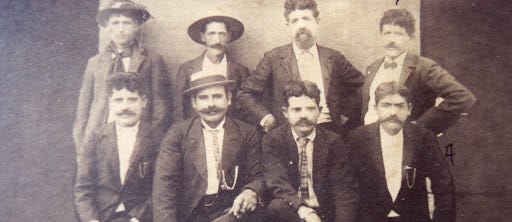

ALMOST WHITE

The Madeirans were well received by the authorities, who regarded them as a buffer class between White and Black (not that said authorities deigned to mix with them, seeing them as far too low class). Not only did they bring their labour (though almost all fled the wretchedness of indentureship as soon as they could), but they also brought new and in-demand levels of expertise and entrepreneurship. Generally better educated than the other indentured immigrants, they saw their new lands as places of opportunity. Among them were traders with strong fiscal connections as well as seasoned farmers and fishermen. Soon they became the nations’ shopkeepers. Their liquor experience meant that they virtually started the rum business in the southern Caribbean (and they went on to own most of the rum shops); they were involved in the beer business in Barbados (a Madeiran was one of the founders of that nation’s Banks beer); and they reshaped the food profile where they settled, even though this profound food legacy is largely unrecognised and uncredited.

Stay tuned.

and don’t forget my book is out. check for it on Amazon